8. The Meizan Studio (1880–1941) : Yabu Meizan and Yabu Tsuneo

Introduction

The name Yabu Meizan (藪明山) is synonymous with the finest Satsuma ware, renowned for its technical precision, subtlety, and refined artistic choices—qualities that distinguished it from the more opulent and commercial ceramics of the time. In this context, Yabu Meizan refers not only to the celebrated artist himself, but also to the studio and brand he established. By using the name Meizan Studio, we aim to highlight that Yabu Meizan’s success was largely built on his reliance on a team of exceptionally skilled yet anonymous ceramic painters, who were instrumental in producing the exquisite works attributed to him. It is therefore important to view Yabu Meizan not only as a gifted individual artist, but also as a shrewd entrepreneur and the architect of a carefully cultivated brand.

After Yabu Meizan’s retirement in 1926, leadership passed to his adopted son, Yabu Tsuneo (藪恒夫), who directed the studio until his death in 1941—marking the end of the Meizan Studio. The term is therefore used here to refer to the studio’s full lifespan, from its founding in 1880 to its closure in 1941. Especially the role of Yabu Tsuneo (rarely referred to as Meizan II) in the studio, remains relatively little known in the West.

By examining both figures separately, we try to clarify their individual contributions.

The Yabu Meizan Studio

View of the Meizan Workshop in 1931 The sign reads: YABU MEIZAN SATSUMA PORCELAIN. Standing in front of the gate are Tomeko Meizan (left) and Kazu (right), grandchildren of Yabu Meizan.

Yabu Meizan (1853-1934) 藪 明山

Artist, Entrepreneur, Innovator

Born Masashichi Yabu on January 20, 1853, in Nagahori, Osaka, Yabu Meizan came from a distinguished lineage rooted in art and scholarship. His grandfather, Yabu Kaku-dō (1773–1849), was a respected Confucian scholar and calligrapher from Awaji Island, while his father, Yabu Chōsui (1814–1867), was a celebrated Ukiyo-e artist known for landscapes and bird-and-flower compositions. As the second son, Yabu was raised in an environment where art and culture were central to daily life.

In 1860, he became heir to the Yabu Sukezaemon family and moved to Fukura on Awaji Island. There, he studied calligraphy and classical literature under the head priest of Shinkōji Temple, and later received instruction in Chinese classics and painting from Tadokoro Atsurō, a samurai from Sumoto. At age fifteen, with the dawn of the Meiji era in 1868, Yabu relocated to Osaka to pursue commercial training.

Early accounts suggest that Yabu felt a strong calling toward the arts and traveled to Tokyo in 1880 to study ceramic painting. His training lasted from April to October. On returning to Osaka that same year, he founded a studio in Nakanoshima specializing in richly decorated Satsuma ware. He sourced unglazed pottery from renowned kilns such as Kinkozan in Kyoto and Chin Jukan in Satsuma. We presume that Yabu Masashichi began using the art name (go) of “Yabu Meizan” or “Meizan” at or around this date.

Although Meizan referred to himself as a tōgakō (“ceramic painter”), nonetheless it remains uncertain whether he truly possessed the technical skills to justify that title (in: Tomoko Nakano in “Yabu Meizan in 1880”). A more nuanced understanding of his brief time in Tokyo may be found in the phrase kanzuru tokoro (“the place of inspiration”), as described by Tsuneo in the posthumously compiled Business Biography of the Late Yabu Meizan. This suggests that his stay was less about formal training in ceramic painting—training which, in any case, would have been too brief to develop the necessary expertise. Moreover, available sources offer no evidence that he studied painting under his father, the accomplished artist Yabu Chōsui. It is therefore plausible that Meizan’s own painting abilities—particularly in the early years of the studio—were insufficient to account for the exceptional quality of the works produced under his name.

Yabu Meizan

Mark of the Meizan Stuido - Yabu Meizan period

Yabu Meizan used his marks as a logo

What Meizan did excel at, however, was establishing a strategic artistic direction for the studio. He developed designs of high aesthetic quality that resonated strongly with Western tastes, rather than following the trend of commercially driven ceramics of the time. He quickly proved himself not only a gifted designer but also a shrewd entrepreneur. As the studio expanded rapidly, in 1888 he relocated to Dōjima in Osaka and begin selling directly to foreign clients.

A key factor in his success was his partnership with Yoichiro Hirase, a Christian dealer in Satsuma ware with ties to American Board missionaries. Hirase’s values of honesty and sincerity aligned with Meizan’s own, and their collaboration opened new international channels for high-end Satsuma ware—beyond the traditional framework of exhibitions. Meizan himself converted to Christianity and deliberately sought a partner who embodied trust, transparency, and global reach.

In 1895, Meizan adopted Tsuneo, born into the Nakanishi family in Tsuyama, as his heir. Tsuneo inherited both the Yabu family name and the studio, becoming Yabu Tsuneo. It is likely that, as successor-in-training, Tsuneo played a role in both the artistic and commercial sides of the studio. Meizan’s early acclaim allowed him to pursue broader ambitions, and his biography includes an impressive list of national and international exhibitions where he served as promoter, advisor, or committee member. Meizan was a key figure in Osaka’s industrial, educational, and cultural development during the Meiji era, and his frequent travels made shared leadership of the studio a practical necessity.

A rinsing bowl, probably from the founding years of the Meizan Studio 1880-1885. (Osaka Museum of History)

The studio’s work is distinguished by microscopically fine painting, harmonious compositions, and a rich yet restrained use of gold and enamel. According to Impey & Farley in Treasures of Imperial Japan, several characteristic phases can be identified in Meizan’s painting style and choice of subject matter. However, it should also be noted that dating Meizan’s works can be problematic, since there was sometimes a considerable gap between the time of production and their first exhibition.

The earliest phase remains relatively obscure; we found only one surviving example: a rinsing bowl with a design reminiscent of traditional Satsuma and a border decoration which, according to Tomono Nakano, does not appear to be executed with particular skill. However, the studio’s quality improved rapidly. By 1885 Meizan had already won his first prize at a major exhibition, and from the late 1880s his works also began to be exported.

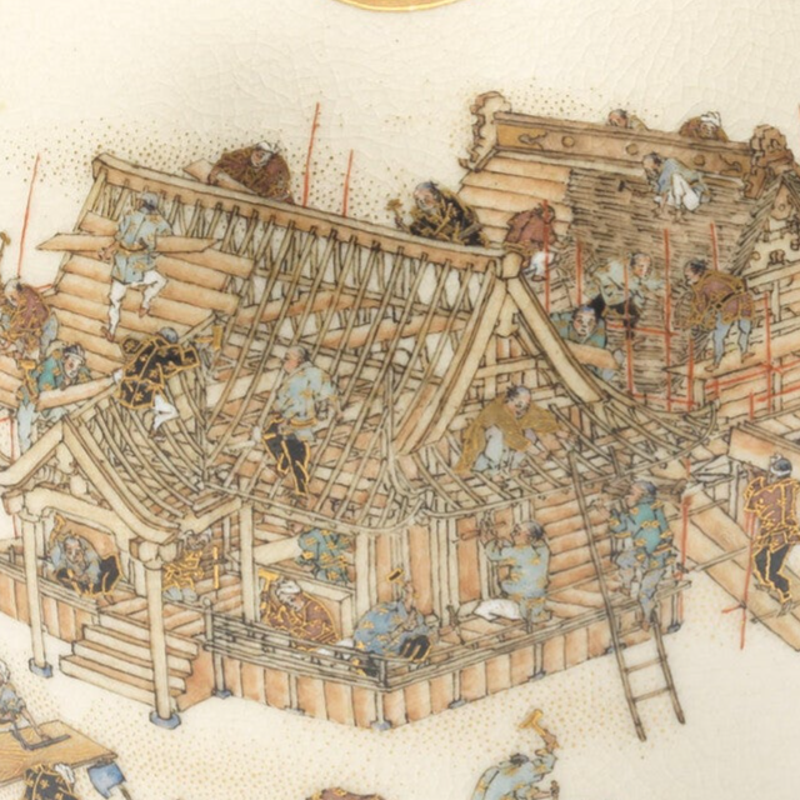

Early pieces often featured Chinese and Buddhist motifs, but around 1890 Meizan shifted toward distinctly Japanese themes—festivals, landscapes, and scenes of daily life—intended primarily for export to Europe and the United States. Between then and 1910, the Meizan studio created works that rank among the finest Satsuma ware ever produced: exquisite landscapes and miniature scenes teeming with dozens of figures, rendered with obsessive attention to detail so minute that they had to be magnified to be fully appreciated. Many of his subjects held documentary value, depicting everyday life and celebrated destinations such as Lake Biwa and the Itsukushima Shrine.

A wonderful example of Meizan's craftmanship on an 11 cm small vase, with detailed scenes depicting numerous craftsmen and artisans engaged in different tasks during the completion process of two Shinto shrines.

L' Exposition Universelle de Paris 1900

The Japan -British Exhibition of 1910

Yabu Meizan always put a lot of energy into major international exhibitions, and his work gained recognition at many exhibitions in Japan and abroad, especially in Paris (1900), St Louis (1904), and London (1910), he visited each venue and played an important organisational role. Yabu Meizan is therefore considered, especially in the West, one of Japan's greatest Satsuma artists. He created a new form of intricate artwork and his early artworks were so detailed that one needed the help of a magnifying glass to appreciate the fine miniature painting. But also after 1910, when he returned to more simplified designs, he always retained the highest attention to detail.

Meizan drew inspiration from copperplate engravings sold to tourists in Kyoto and Osaka, and he experimented with copperplate transfer techniques to reproduce designs quickly and consistently. This allowed him to repeat floral and ornamental motifs with remarkable precision, creating a sense of visual balance reminiscent of European wallpaper design.

A copperplate print of a daimyo procession used by Yabu Meizan

A bowl depicting a daimyo procession, ca 1910

As shown on this vase Yabu Meizan returned after 1910 to more traditional Japanese views of aesthetics, with greater use of negative space

From the end of the Meiji period, around 1910, Meizan’s style suddenly changed. He began to favor compositions with a single motif, leaving the surrounding surfaces undecorated. This approach reflects the Japanese concept of yohaku no bi—the “beauty of emptiness”—an aesthetic principle in which visual harmony emerges from the balance between the filled and the unfilled or unpainted space. Commercial considerations may also have played a role in this shift. Before 1910 his work was densely decorated, in line with Meiji-era export expectations. Yet after the Chicago World's Fair of 1893 and certainly after the 1900 Paris Exposition, Japan faced criticism for “corrupting” its traditional art to suit foreign preferences. In response, Meizan adopted a more restrained style, often using a single motif such as maple leaves. This change may reflect both a personal deeper appreciation of authentic Japanese aesthetics and a strategic adaptation to market trends. However, this new style proved unsuccessful. Western buyers largely preferred his previous Satsuma ware and moreover increasingly shifted their interest toward Chinese ceramics. This shift, combined with the economic challenges brought on by World War I, further strained the viability of the Meizan Studio.

According to Nakano Tomoko in “The ‘Ceramic Painter’ Yabu Meizan and His Artistic Practice” (p. 19), “As far as can be ascertained, production continued in the workshop until the Taisho period, but ceased thereafter.” In her original Japanese text, she uses the phrase 大正年間までは, which translates literally as “until the years of the Taisho period,” rather than “up to and including the Taisho period.” This nuance suggests that production likely stopped sometime during the early Taisho years, approximately between 1912 and 1916. This interpretation aligns with the absence of any known works from the Yabu Meizan Studio dated to the later Taisho period.

It is believed that the Meizan Studio continued to operate by selling previously completed works until the early Showa period, prior to the outbreak of WW II. Despite the declining demand for Satsuma ware in the years leading up to the end of production, Meizan remained steadfast in his commitment to quality. His focus on refinement and consistency set his work apart from mass-produced ceramics, underscoring his dedication to artistic excellence even in difficult times.

Yabu Meizan was not only a master art director but also a product of his time. The Meiji era was marked by modernization and Western alignment, balanced with a desire to preserve Japanese identity. The Japanese government promoted traditional arts such as ceramics, lacquerware, and metalwork as national heritage, showcased at expositions in Vienna (1873), Paris (1878) and beyond. Meizan actively contributed to this effort, building overseas networks and helping organize major exhibitions in Chicago (1893), Paris (1900), St. Louis (1904), London (1910) and San Francisco (1915). He pursued efficiency in production while remaining true to his artistic ideals, elevating Satsuma ware from craft to art and earning acclaim in the West.

A business card from the Yabu Meizan Studio

A large 37 cm plate with karako boys and an enormous white elephant - Kahilili Colllection

As previously noted, Tomoko Nakano has argued that Yabu Meizan may not have possessed the technical skills required to execute overglaze decorations himself. Nonetheless, Yabu Meizan fully deserves recognition as the artistic director and innovator behind the studio’s output. The creations produced under his leadership represent some of the finest achievements in the history of Satsuma ware, reflecting a rare blend of technical mastery, cultural depth, and international appeal. More than a studio, the Yabu Meizan workshop became a center of artistic innovation that embodied the spirit of the Meiji era. He retired in 1926, passing the studio to Yabu Tsuneo, and died on May 2, 1934. His funeral was held at the Naniwa Church in Osaka.

Marks and Seals

The article Satsuma Yaki and the Satsuma Pottery Dealer Hirase Yoichiro (Osaka Historical Museum) highlights Yabu Meizan as a smart entrepreneur. From the outset, his studio was envisioned as a high-end brand that fused artistic excellence with strategic branding and commercial foresight, where corporate identity played a crucial role and a consistent signature can help to establish this. The name “Yabu Meizan” became synonymous with quality Satsuma ware, marked by consistent stylistic traits and a limited set of signatures: “Yabu Meizan” in a cartouche, “Meizan sei” in a cartouche, and “Meizan” alone. The last one however was only used by his successor Yabi Tsuneo. Most distinctive is the rendering of the left radical in the kanji 明 as a circle with a dot—except for one known exception, which, as Louis Lawrence notes, was reserved for works of exceptional quality.

It should be noted that several other Satsuma artists also signed their work with the name Meizan, either using the same spelling or different kanji characters. Most of these artists can easily be distinguished from Yabu Meizan, as their signature styles and overall quality differ significantly. That said, only the Meizan from Kanazawa—identified by Louis Lawrence—poses a genuine source of confusion. His work is of comparable quality, and his signature, 'Meizan Sei,' bears a notable resemblance.

An example of the work and the "Meizan sei" mark of Meizan fom Kanazawa, not Yabu Meizan (acc. to Louis Lawrence)

Our wares all bear this mark: Meizan's mark as a corporate identity symbol

While a few early pieces bear the “Meizan sei” mark, probably all from the early nineties, the dominant signature afterwards is “Yabu Meizan” as a seal mark in gold within a square cartouche. Before 1900 this mark appears in gold on a white ground, but from this time all Yabu Meizan’s works were signed with his seal mark written in gold on a different colour gold ground. This consistency suggests it functioned as a typographic logo, reinforcing brand identity and trust—similar to Kinkozan’s use of marks like Kinkozan–Made in Japan” for Art Deco pieces and “Royal Nishiki Nippon” for his Nippon ware. The use of the mark as a corporate identity symbol is clearly evidenced by th studio's own advertisements.

This mark "Dai Nippon Meizan sei" was reserved for exceptional pieces

"Meizan sei"assumably not later as early 1890's

"Yabu Meizan" in gold on white ground, assumably not later as 1900

"Yabu Meizan" in gold om (gold) colored ground, assumably always after 1900

Yabu Tsuneo (藪恒夫,1868–1941) or Meizan II (明山二代)

Heir to the Meizan Legacy

Yabu Tsuneo was born in 1868 in Tsuyama, Okayama, into the Nakagawa samurai family. In 1883, he was adopted by the biological mother of Kayo, the wife of Yabu Meizan, making him Meizan’s brother-in-law by adoption. Twelve years later, in 1895, Tsuneo was formally incorporated into the Yabu family and designated as Yabu Meizan’s legal heir. Unlike Western notions of adoption, which often center on child welfare, Japanese adoption—especially of adults—served as a strategic means to preserve family lineage, social status, and property. Tsuneo’s adoption must be understood within this cultural framework: it was a deliberate move to secure the continuity of the Yabu legacy, particularly as Yabu Meizan’s ceramics enterprise was gaining international acclaim. Tsuneo would eventually succeed him as the second Meizan (ie Meizan II).

It remains uncertain whether Tsuneo received formal training in ceramic painting during his early years. However, it is certain that he was already active in Meizan’s studio prior to his official adoption in 1895. An article in the Manchester Guardian from 1891 (quoted in Louis Lawrence’s Satsuma: The Romance of Japan, p. 252) refers to him as Yabu Meizan’s brother—Tsuneo had not yet been adopted—and notes his involvement in establishing a line of modern Satsuma ceramics. His appointment as heir may well have marked the culmination of a long apprenticeship, suggesting he had acquired the necessary skills and experience to co-manage the studio alongside Yabu Meizan.

After Yabu Meizan’s retirement in 1926, the studio was formally transferred to Tsuneo, who led it until his death in 1941—bringing the Yabu Meizan Studio to a close. According to family records, the studio itself was destroyed in 1944 during an allied bombing of Osaka.

Portrait of Yabu Tsuneo

The mark of Yabu Tsuneo / Meizan II

View of the Meizan Workshop in 1931 The sign reads: YABU MEIZAN SATSUMA PORCELAIN. Standing in front of the gate are Tomeko Meizan (left) and Kazu (right)., grandchildren of Yabu Meizan.

Documentation regarding the division of responsibilities in the years leading up to Yabu Meizan’s retirement is limited, and what follows should be viewed as interpretative rather than definitive. Sources from that time indicate that Meizan was deeply involved in establishing overseas sales channels and held numerous positions on boards and committees related to international exhibitions and world fairs. His frequent appointments as secretary and committee member reflect his sustained engagement in the industrial, educational, and cultural development of Osaka during the Meiji period. In contrast, there is no evidence that Tsuneo participated in these external activities. This may suggest a functional division within the studio: Yabu Meizan as the public face and cultural ambassador, and Tsuneo as the figure responsible for internal operations and day-to-day management—though certainly under Yabu Meizan’s direction.

The structure of the Yabu Meizan Studio appears to have supported such a division. As Yoshie Itani observed in The Design Philosophy of Yabu Meizan, “He did not remain an independent craftsman, but built a studio around himself and recognised his role as an art producer.”

This model required Meizan to surround himself from the outset with highly skilled ceramic painters who could execute his designs under his name and direction. In this context, the creation of artistically high-quality and even exceptional Satsuma did not depend on Meizan’s constant presence. While he likely shaped the artistic direction, contributed designs, and introduced innovations such as copperplate transfer printing, it is suggested that the supervision of production could—after 1895 —be entrusted to Tsuneo.

Compared to Yabu Meizan, the work of his successor Tsuneo is less documented, rarer, and generally less appreciated. While Meizan’s creations were celebrated internationally during his lifetime and continue to be highly valued in museum collections, Tsuneo—though loyal to the stylistic tradition—favored expressive facial features and humorous scenes over the meticulous micro-detailing that defined Yabu Meizan’s hallmark style. A striking example is this vase depicting the Hyakki Yagyō (Night Parade of One Hundred Demons), inspired by the work of Kawanabe Kyōsai. Despite its strong design and execution, Tsuneo’s work has garnered less recognition—a disparity also reflected in auction results.

A Yabu Tsuneo vase depicting the Hyakki Yagyō (Night Parade of One Hundred Demons), inspired by the work of Kawanabe Kyōsai - 12 cm. ca. 1930 / Galerie Zacke -Vienna

Tsuneo’s relative obscurity can also be attributed to his limited output. As previously noted, although the Meizan Studio remained active until 1941, actual production likely ceased much earlier, around 1916, with operations shifting toward the sale of existing inventory. This makes the existence of Meizan pieces attributed to Tsuneo and dated after 1926 all the more intriguing. Although he led the studio from 1926 until his death in 1941—a span of fifteen years—the number of such works appears to be very limited, suggesting they were produced only sporadically and likely not beyond the early 1930s. Interestingly, all known pieces are small to very small in scale—perhaps intended to highlight the kind of intricate detail that once made Yabu Meizan a celebrated figure in Satsuma ceramics. Despite the modest sample size, there is a surprising diversity in design, motif, and decoration. These range from kinrande-style and fully painted surfaces to more understated compositions with generous white space. The images include Japanese daily scenes, mythological figures, monkeys, birds, and even a millefleur-like arrangement featuring hundreds of butterflies and insects. When it comes to quality—both in design and execution—Tsuneo’s work seems, at times, to fall short of Yabu Meizan’s standards. Some compositions feel overly busy, lacking the balance and subtlety that characterized Meizan’s finest pieces. This is particularly noticeable in the depiction of monkeys and the use of dotting techniques, where the craftsmanship appears less refined.

Taken as a whole, the work gives the impression of drawing heavily on established traditions, with limited signs of artistic renewal. This impression may reflect the broader historical context: the late Taisho and especially the Showa periods were not generally associated with innovation in Satsuma ceramics, which had begun to lose their relevance much earlier.

pair of gourd shape vases Bonhams Los Angeles – post 1926 -14.9 cm

pair of vases with figures in a garden, the neck with butterfly decoration, the Auction Rooms, Surrey - post 1926 11.5cm.

bowl with multiple insects and butterflies decorations - post 1926, w. 12,1 cm h. 5.8 cm

Vase with raised gold decorations of birds behind net, ass. post 1926. 11 cm

Vase with raised gold decorations of aristocrats and various floral, other decorations , ass. post 1926. 9,5 cm

A candlestick with butterflies - Bonhams Edinburgh. 19.5cm

a flat, oval vase with monkeys and sparrows decoration, Zacke gallery Vienna, post 1926-12,8 cm.

We believe that Yabu Tsuneo, upon taking on the title of Meizan II, made a genuine effort to revive production at the Meizan Studio after a long period of inactivity. Unfortunately, this renewed attempt was quickly overshadowed by the economic downturn of the Great Depression and the rising tensions of an approaching war—circumstances that posed serious challenges for any ceramic workshop. The closure of the much larger Kinkozan Studio in 1932 clearly illustrates the broader difficulties of the time.

In that context, comparing Yabu Meizan and Yabu Tsuneo directly isn’t easy—and perhaps not entirely fair. Meizan founded the studio and developed its artistic identity during the vibrant Meiji era, a time of cultural growth and international recognition. Tsuneo, by contrast, inherited a studio whose production had already ceased, and was tasked with its leadership during a time defined by socio-economic constraints and looming conflict.

Although history has understandably placed Tsuneo in the shadow of his illustrious predecessor, he remains a vital part of the Meizan Studio’s legacy and deserves greater recognition within its historical narrative. For that reason, his role is emphasized here more explicitly than is typically the case in reviews of the Meizan Studio.

Marks and Seals

The Meizan seal as shown here is attributed to Yabu Tsuneo. Although its exact dating remains uncertain, experts such as Lawrence and renowned auction houses like Bonhams suggest that this signature emerged after 1926. It differs from the original Yabu Meizan seal by omitting the family name "Yabu," yet retains a distinctive feature: the left radical of the kanji 明 is rendered as a circle with a dot. While Tsuneo may have contributed to pre-1926 works during a transitional phase (if there was any between 1916 and 1926), the studio’s signature was the Yabu Meizan seal mark, and the decisive factor in matters of attribution.

It is highly unlikely that Tsuneo signed works as 'Meizan' before 1926, as 'Meizan' was the gō (art name) of Yabu Meizan, adopted in line with iemoto traditions. Tsuneo was only recognized as the second-generation Yabu Meizan in 1926 and was not authorized to use the name earlier. Notably, he never signed as 'Yabu Meizan II,' but simply as 'Meizan,' likely to capitalize on the brand’s prestige while downplaying the shift in leadership.

The question arises whether Yabu Meizan used the simple 'Meizan' mark during the founding years of his studio, prior to adopting the 'Yabu Meizan' seal. The two vases with raised gold decoration above bear the 'Meizan' signature attributed to Tsuneo, yet stylistically they could date to 1880–1888, before the studio relocated to Dōjima, Osaka. As no comparable early works are known, we currently believe Tsuneo experimented with several outdated styles to revive Meizan Studio production from 1926 onward, and therefore the specific 'Meizan' mark should be attributed to Yabu Tsuneo.

Closing Remarks and Discussion

When reading the above, it’s important to keep a few considerations in mind. Much of the information is drawn from the work of Nakano Tomoko, who has conducted extensive research on Yabu Meizan over many years and is one of the few scholars to use direct historical sources, including family archives and Tsuneo’s own notes on his father’s life. However, historical sources are often fragmentary and require personal interpretation. Several points warrant further clarification, especially given the limited availability of information on Yabu Meizan and his studio—particularly studies based on contemporary documentation. The following section addresses some of these issues that call for deeper discussion.

The artist Yabu Meizan

Yabu Meizan as an old man

Yabu Meizan was a celebrated figure in his time, widely admired for the astonishing precision and delicacy of his work. It is now generally accepted that he relied on highly skilled ceramic painters to achieve such detail. Although he referred to himself as a tōgakō (陶画工), it is unlikely he possessed the technical expertise required for that role. A tōgakō is a specialized ceramic painter with deep knowledge of pigments, glazes, and their behavior during firing—skills that demand years of training in a dedicated environment. There is no evidence that Yabu underwent such training nor was he born in a family of ceramic artists, as Kinkozan or Taizan Yohei was. However, his drawing and design skills were likely highly developed, shaped by his father's artistic background and his early studies in classical Chinese painting under Tadokoro Atsuro. He had a clear grasp of anatomy, composition, and color theory, and an undeniable talent that enabled him to create exceptional designs. We therefore believe that his true talent, lay not in the execution of decoration but in his role as designer and innovator of Satsuma ware during the Meiji period.

For decades, the Meizan Studio produced some of the finest Satsuma ceramics imaginable. Each artisan had a distinct role: master decorators rendered exquisite designs on surfaces barely a few square centimeters wide, while junior painters or apprentices focused on coloring or applying transfers. At the center stood Yabu Meizan himself, guiding the studio as art director, pioneering new decorative styles through copperplate etching, and establishing a network of international buyers—transforming Satsuma ceramics into a global art form.

The entrepreneur Yabu Meizan

Yabu Meizan was not only a true artist but also a shrewd entrepreneur. He skillfully leveraged the economic opportunities of the Meiji era without resorting to mass production. His commercial instincts even preceded his interest in ceramics—he began studying commerce in 1868 and was actively involved in business, as noted in both the Meizan Record and Business Summary. Though the nature of his early ventures remains unclear, he was likely a rice merchant and later held numerous advisory roles in industrial organizations, earning significant recognition.

In 1880, Meizan turned to ceramic painting and soon established his own studio. His strategic mindset was evident in the location of his workshops—first in Nakanoshima, then Dojima—chosen for their proximity to waterways and train stations. A master networker, he combined high-quality craftsmanship with sharp business acumen. His partnership with Yoichiro Hirase opened doors to international markets, and his organizational talent made him a key figure in national and global exhibitions. In doing so, he contributed significantly to the dissemination of Japanese art and culture—an important objective of the Meiji government. His efforts garnered considerable recognition and elevated his public profile, culminating in 1895 with the distinguished honor of a personal audience with Emperor Meiji during the latter’s visit to an exposition.

Yabu Meizan was, in many respects, a pioneer of his time. He ran his Satsuma workshop not merely as a traditional artisan, but as a true art producer—combining exceptional craftsmanship with a sharp focus on business and operational strategy. This dual approach directly influenced the quality and innovation of his work. He introduced new production techniques, such as specially developed copper plates for applying decorations onto glaze. These innovations enhanced quality control, enabled greater precision and standardization, and strengthened the studio’s operational stability. They also paved the way for intricate new styles, including the celebrated millefleur decoration.

Remarks on the production and continuity of the Meizan Studio

Literature suggests that production at the Yabu Meizan Studio came to a halt in the early Taishō period. From that point on, sales were made exclusively from existing stock—a situation that lasted until Tsuneo’s death in 1941. This is supported by a 2005 bulletin from the Osaka Museum of History, which notes: “Production at Meizan’s studio was coming to its end after the Japan-British exhibition held in London in 1910.” An interview with Meizan in The Studio (1910) further confirms this, stating: “He is a little over sixty and does not work so much at the present.” These sources reinforce the view that output had already declined by the early Taishō years. Yabu was a businessman who understood the economic realities of his time. He recognized that producing and retaining staff without sufficient demand was unsustainable—a reasonable assumption, all things considered.

However, this raises questions. It seems unlikely that the studio’s inventory was large enough to sustain operations for over two decades. If expert conclusions are accurate, we must consider what this implies—particularly how income may have been generated during that prolonged period of apparent inactivity.

Several possibilities may explain the studio’s prolonged activity. One is that it held a substantial inventory. While Meizan’s workshop was much smaller than Kinkozan’s—whose grandson cited an annual output of 400,000 pieces—a sizeable stock is plausible. Nakano suggests that production under the “Yabu Meizan” name may have extended beyond Meizan’s own studio, with some works outsourced to Kinkozan’s Kyoto ateliers, which supplied blanks and employed skilled decorators.

Not all Meizan pieces were of exceptional quality; more utilitarian items like tea sets were also produced and possibly subcontracted, implying a larger inventory than the studio’s reported staff size would suggest. However, when the Meizan Studio was destroyed in June 1945, ledgers, inventory lists, and similar records were also lost, making it difficult to answer this question with factual certainty

A tea set comprising a tea pot, creamer, sugar bowl and two cups and saucers - Bonhams

Another possibility concerns Nakano’s use of the term 完成品 (“finished product”), which refers to a completed item ready for sale but does not indicate its origin. This opens the possibility that Meizan sold not only his own work but also pieces made by other producers, potentially on commission and not necessarily signed by him.

Finally, it is likely that Yabu Meizan had additional sources of income. Throughout his life, he was active in various commercial, industrial, and cultural ventures—some officially registered at his residence. He was also a sought-after advisor, and records show he continued receiving honors into the 1920s and 1930s, including invitations to present his work to Japanese and foreign royalty, some of whom became his patrons.

This offers little clarity on how Yabu Tsuneo managed to keep the studio open during the economically difficult years leading up to World War II. Although he attempted to restart production, the small number of known works suggests output was limited—likely only in the early years after Meizan’s retirement. The studio’s reputation was largely tied to Yabu Meizan himself, and Tsuneo is not known to have had the same network, advisory roles, or honors that his predecessor enjoyed and may have capitalized on. Nakano emphasizes that after Tsuneo’s death, both Yabu Meizan—once a celebrated figure in prewar Osaka—and the ‘Yabu Meizan’ brand largely faded from memory in Japan. It was not until 1991, through the efforts of his descendants, that his legacy was rediscovered and regained prominence through major exhibitions.

Notes on the studio’s signature marks

The final point requiring clarification concerns the signature. It is clear that Yabu Meizan, and by extension the Meizan Studio until his retirement, used the gold 'Yabu Meizan' seal, as confirmed in his advertisements. However, it remains uncertain when this practice began. Stylistically, the gold 'Meizan Sei' seal appears to be a precursor. There is no documentation of how he signed works during the studio’s early phase, which began in 1880 and received its first recognition—a bronze medal—in 1885. Could it have been the plain 'Meizan' mark later attributed to Tsuneo? Most of Tsuneo’s works align stylistically with the period when the 'Yabu Meizan' seal was consistently used. Yet, two known pieces could plausibly date from the early 1880s, suggesting that Yabu Meizan may have initially signed with the plain 'Meizan' mark before introducing the 'Meizan Sei' and 'Yabu Meizan' seals. In that case, Tsuneo may have reverted to the early 'Meizan' mark from 1926 onward. He was, after all, entitled to use the Meizan name, yet chose to distinguish himself from it—perhaps out of respect for the works produced under his predecessor’s name. This remains speculative, as almost no works from the studio’s earliest phase have been identified, and researchers such as Nakano have not addressed the issue of Meizan’s initial signature.

Conclusion

The legacy of Yabu Meizan and the continuity of his studio under Tsuneo raise complex questions that remain partially unresolved due to the fragmentary nature of historical sources. While Meizan’s role as a visionary designer and strategic entrepreneur is well established, the exact dynamics of production, authorship, and studio operations—particularly in its later years—invite further scrutiny. The possibility of extended inventory sales, outsourced production, and alternative income streams offers plausible explanations for the studio’s longevity, yet lacks definitive evidence. Similarly, the evolution of Meizan’s signature—from the early, possibly plain 'Meizan' mark to the later gold seals—adds another layer of ambiguity, especially in light of Tsuneo’s use of the original mark.

While not all questions can be answered, there is ample evidence to confirm that the history of the Meizan Studio is remarkably compelling. It captures both the brilliance and the ambiguity of a transitional era in Japanese ceramic art—from the Meiji to the early Shōwa period—an age shaped by innovation, commerce, and the enduring mystery of artistic identity. The studio’s masterpieces were conceived by an exceptionally talented and celebrated designer, yet brought to life by anonymous artisans whose collective craftsmanship resulted in works of extraordinary beauty that are still admired and collected by many today.

Main references:

Nakano Tomoko: “Ceramic Painter” Yabu Meizan and His Artistic Practice: A Preliminary Study on the Transfer Technique Using Copper Plates for Underdrawings- Osaka Museum of History Research Bulletin Volume 19, Pages 19-38, March 2021

Nakano Tomoko: Yabu Meizan in March 1880 - Osaka Museum of History Research Bulletin Volume 23, Pages 27-42, March 2025

Nakano Tomoko: Yabu Masashichi / Meizan Personal Record - Osaka Museum of History Research Bulletin Volume 17, Pages 61-72, March 2019

Nakano Tomoko: Yabu Meizan and the Distinguished Satsuma Ware Dealer Yoichiro Hirase - Osaka Museum of History Research Bulletin Volume 20, pages 1-19, March 2022

Yoshie Itani: The Design Philosophy of Yabu Meizan: Landscapes of Western Japan in Copperplate - The Journal of the Conference of Design History and Theory, paper/ 2019, 8, p. 72-78

Yoshie Itani: The Glorious World of Yabu Meizan : Comparing the Heisei Memorial Art Gallery and Khalili Collections - The Journal of the Asian Conference of Design History and Theory, paper/ 2022, 4, p. 32-40

Louis Lawrence: Satsuma: The Romance of Japan - Meiji Satsuma Publications 2011

Oliver Impey, Malcolm Fairley: Treasures of Imperial Japan. Ceramics from the Khalili Collection, Kibo Foudation 1994

Kinkozan Kazuo: New Discoveries & Insights on Osaka Satsuma: Yabu Meizan -Awata-yaki & Kyoto Satsuma Blog 16-04-2021

Some masterpieces of the Yabu Meizan Studio

Maak jouw eigen website met JouwWeb