Satsuma: A brief history

Historical context

The history of Satsuma pottery cannot be seen separately from the history of Japan itself, because it is interwoven with the opening up of Japan after centuries of isolation, leading to an explosive demand for Japanese products from abroad and the need to produce in a way completely different as in the centuries before. But the history of Japan is long and not everything is equally relevant in this context. We therefore limit ourselves to what is necessary to understand the origin and further development of Satsuma pottery.

The history of japan can be broadly divided into 5 periods:

Kodai, or the Old Age, about 10000 BC. -1192

Chusei, or Mid-time period, 1192-1600

Kinsei, or Modern time (Recent past), 1600-1867

Kindai, or Recent time, 1868-1945

Gendai, or Current time, 1945-present

Important for a good understanding of Satsuma pottery are the Kinsei period, which coincides with the period called EDO, and Kindai, which coincides with the periods called MEIJI, TAISHO and first SHOWA up till 1945.

Also important is to understand the role of the Emperor within the social system and the balance of power of Japan. The Japanese emperor or tennō in Japanese was seen as a direct descendant of the sun-god Amestarusa from ancient times till the collapse of Japan in 1945, when Hirohito denied that he was a god and settled for a strictly constitutional and representative task. Until that time the Emperor was considered divine and therefore inviolable. Despite this inviolability, the worldly power of the emperor was limited, with mainly religious functions within the shinto, the eldest religion of Japan. Although the Japanese emperors were powerful in the early and mid-period, much political and military power fell into the hands of the emperor's advisers at the beginning of the seventh century. These advisers however still needed the permission of the emperor in their decisions, since he had divine authority over everything. The role of the emperor changed during the twelfth century when the advisers were replaced by feudal warlords called the Shogun. At the end of the 12th century, Shogun Minamoto no Yoritomo, member of thet powerfull Minamoto family, installed a shogun-representative in every province. These local rulers later were called daimyō. It made that Yoritomo became de facto the ruler of Japan and the tennō only reigned in name.

After the Minamoto period, the shogunate came into the hands of the Ashikaga family (1336-1573). However, the power of the shogun was much less during this period: the local daimyō, became more and more powerful, and the power of the Ashikaga family was mainly based on their contacts with these daimyō. Later the central authority in Japan disappeared altogether, and although the Ashikaga family remained shogun until 1573, their position in the 16th century was only a paper power. Japan was a divided country, the individual provinces were independently governed by the daimyō.

This changed after the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600, one of the most important historical events of Japan. The conflict took place at Sekigahara between two of the most powerful clans of Japan and their allies: an army of daimyō loyal to the Tokugawa clan versus an army loyal to Toyotomi Hideyori, the heir to the Taikō. The Battle was won by the Tokugawa clan. and this victory allowed the Tokugawa family to establish their Shōgunate which formed the basis for the unification of Japan. The first Tokugawa Shogun, Ieyasu, was installed by the Emperor of Japan in 1603, the start of a new period in Japanese history. The Tokugawa would be the most powerful clan to be and ruled for 265 years with supreme power. The previously so powerful position of the daimyo became secondary to that of the Shogun. The emperor resided in his court in the capital Kyoto but without any power, while the Shogun ruled the country in Edo, today's Tokyo. The Tokugawa period is therefore also known as the Edo period.

The Tokugawa dynasty has had a major impact on life in Japan. The most important of these was the the sakoku, the isolation policy of the ‘closed country’, which began in 1600, leading in 1609 to a ban on Christianity and became a fact in 1641 when all Westerners had to leave Japan, with exception of the Dutch, who were allowed to retreat to the island of Deshima. For two centuries this small enclave of a few square kilometers was the only link between Japan and the West.

The Edo period was a period without major conflicts or wars. As a result, the importance of military power declined, and many samurai became bureaucrats, teachers or artists. During the Edo-period the Daimyo changed from warlord to a patron of the arts, who encouraged the development and perfection of art professions and the cultivation of traditions such as tea ceremony. This certainly also applied to the practice of ceramics, which were initially mainly used for the production of goods that were important for tea ceremony. Many of these Daimyo had their own kilns, and strived for perfection and innovation in the production of ceramics.

battle scene on Satsuma vase

Relative peace prevailed during the roughly 250 years of the Edo Period. However, this changed in the mid-nineteenth century under the influence of Western powers and the increasing dissatisfaction of the Tozama Daimyos (descendants of the daimyos who were not allies of Ieyasu Tokugawa in 1600, including the Daimyo of Satsuma) who wanted to modernize Japan and were thwarted by the continuing policy of isolation of the Tokugawa Shogun. On 3 February 1867, Emperor Meiji (Mutsuhito) took the throne. The power of the emperor grew, he was supported by the progressive Daimyos and his imperial army was equipped with modern weapons supplied by foreign countries. The last shogun, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, gave up his position, but refused to give up all his power. In 1868 the Boshin War broke out between the shogunate and the imperial troops supported by the powerful Tozama daimyos.

Japan's feudal era eventually came to an end in 1868, and the samurai class was abolished a few years afterwards. The Meiji restoration was the start of the modernization of Japan. Western technology was on the rise in the country. Modernization, however, meant the abolition of the old privileges and positions of power of the samurai, something that seriously undermined their financial position. Samurai felt betrayed by the central government, and rebelled, which after some open conflicts was settled in favor of the Emperor. The last war was fought in 1877 by a small group of Samurai and is known as the Satsuma Rebellion.

The Satsuma Rebellion marked the end of the samurai class and the emergence of a new central army without social classes. The emperor became the ruler of Japan, starting a new era of rapid changes what would transform Japan from an isolationist and feudal country to an industrialized and powerful nation.

Development of Satsuma ware

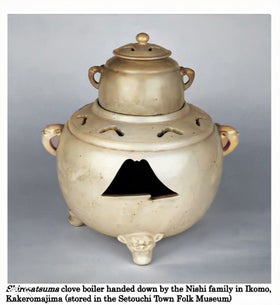

The history of Satsuma pottery starts around 1600 and is closely related to the daimyo of Satsuma, coming from the prominent Shimazu family. After the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate at the beginning of the 17th century the role of the daimyo changed from warlord to the patron of the arts. Korean potters brought the art of pottery to Japan, following Japan's invasion of Korea. Among the army commanders who attacked Korea was Shimazau Yosihiro, the daimyo of Satsuma. When the troops returned to Japan on the orders of the then shogun Hideyoshi, it was Yoshihiro who took a number of Koreans with him, including 14-20 potters who were put to work in Naeshirogawa, Satsuma and in Chosa in the Osuni province what was also ruled by the Shimazu family. Capturing Korean potters was not only out of love for ceramics, but also for economic reasons. Imported Chinese and also Korean pottery ware famous among the higher classes and the price for this type of ceramics was high. An economic reason therefore played a part in specifically capturing potters and forcing them to set up kilns and to use their techniques and skills to serve the Daimyo clan.

The earliest Satsuma pottery, both in Satsuma and Osuni, was made according to a traditional Korean model, and consisted of red or black clay, covered with transparent glaze and without decoration, other than by means of notches in the clay itself (Mishima decoration). The clay that was found was only suitable for the production of black earthenware (Kuro-Satsuma).

In 1617, after many experiments the Korean potters managed to produce white earthenware (Shiro-Satsuma) by clay that was discovered in Naeshiraga and which, after purification of the iron, was suitable for making white pottery. The white Satsuma goods were cherished by the feudal clan and used as official items for the tea ceremony, for their own use or as a gift. The Daimyo highly appreciated the work of the Koreans. From 1675 the status of the potters was equal to the class of Samurai or Goshi (Samurai not living in castles) and they have been granted with the same privileges. Using familynames on official documents, was one of these privileges.

Following the examples of Chinese porcelain and under the constant stimulation of the Shimazu family, more types of decorations were developed and applied, including glazes of a larger color palette and gold dust. The decoration was limited to monochromes, later also sketchy representations, but by no means in the way that would later be applied. This remained the same for a long time, and it was only at the end of the 18th century that a new phase emerged in the production and decoration of Satsuma pottery. Around 1787, two Satsuma potters, Hoshiyama Chiubei and Kawa Yahoro, were sent on a study trip to learn and apply new color glaze techniques to Satsuma pottery in response to the multicolored Imari porcelain produced in Arita on Kyushu Island. On this study trip they also visited Awata, a district of Kyoto. In Kyoto, the potters in the Kiyomizu Kilns were skilled in painting enamel colors on earthenware. Already in the mid-seventeenth century, Nonomura Ninsei (active c. 1646-94) developed the technique of Nishikite decoration, in which polychrome overglaze and gold were applied to light colored clay covered with crackles. It was his descendants who worked in this style and taught the technique of applying multicolor enamel and gold decoration to the Satsuma potters. On their return to Kyushu, the potters of Satsuma began to revolutionize their wares in the last few years of the eighteenth century with a new series of designs, colors and techniques, highly detailed painted decorations with a full color palette and thickly applied gold. Typical of this period, the first half of the 19th century are the floral, stylized or geometric patterns. Shishi, dragons and phoenix were also often depicted. Landscapes and human figures only appeared from the mid-nineteenth century and the ability to create shades of color was also developed during this period.

Satsuma ware after the Meiji-restoration.

It is important to keep in mind that even in this final phase of the Edo era, the balance of power was shifting, yet still intact. But the policy of isolation was increasingly criticized by Daimyos, who saw contacts with foreign countries as a necessary condition for the country's progress. Within the system itself, these first indications for a changing time were not yet visible. The Tokugawa shogunate ruled, and the journey to Edo was still one of the obligations that the Daimyo had to meet. In the production of Satsuma ware, the first half of the 19th century did not bring change, meaning that the kilns were owned or under protection of the Shimazu clan, and that the production of white satsuma was small, and exclusively intended for the Shimazu clan for their own use and as a gift and precious tribute to nobles, including the Tokugawa Shogun. Giving the refined and delicate Satsuma pottery matched the status of the Daimyo as well as the one who received the gift. At the end of the Edo period, the power of the Tokugawa shogunate was waning. Both in Japan itself and by foreign powers, there was a strong pressure to open up the country and making the exchange of culture, trade, technology and science possible.

The emperor Meiji in 1868

This new elan was seen in the Satsumaprovince allready before the Meij restoration in 1868 became a fact. Daimyo Shimazu Nariakira (1809-1858) wanted to promote Satsuma goods as important export goods, and for that purpose the Oniwayaki Kiln was founded, and western enamel and production techniques were studied and applied.

The kiln was continued after his death in 1858 and in 1862 the Shimazu family exhbited their wares at the London International Exposition, it was the first time Satsuma pottery was on display in the west. The very successful exhibition in London was followed by equally successful exhibitions in Paris (1867), Vienna (1873) and at the Philadelphia Centennial in 1876. The reactions were more than positive and triggered a great demand from the West for Satsuma products and more generally for everything that had to do with Japan, a rage which is referred to by the term Japonism.

The Japanese pavilion at the 1867 World Exhibition in Paris.

With the installation of the 16-year-old Emperor Meiji in 1868, the Edo era came to an end; Japan had definitely become part of the international community. The process was accomplished in several stages, resulting in a cenral government and the replacement of the old feudal system with a new oligarchy. In 1871 all Daimyos were required to return their authority to the Emperor. Related to this, the power and privileges of the Shogunate and Damyos came to an end and the abolition of the Samurai class became a fact.

This also had major consequences for the potters and other artisans. They were no longer working under the protection of the Daimyo, and became from that time self- employed craftsmen in a booming market of supply and demand. The overwelming interest in the western world for Satsuma wares after the succesfull exhibitions in London, Paris and Vienna was the main reason for potters all over the country to produce "Satsuma-like" pottery what was in appearance almost indistinguishable with true Satsuma ware.

Mass production of export Satsuma, ca 1900

Satsuma-style pottery was produced or decorated on the Isle of Awaji, Kyoto, Tokyo, Yokohama, Seto, Saga, Kobe and Nagaya. We will not provide an exhaustive overview of all artists working in all places where Satsuma was produced during these years. We limit ourselves to Kyoto, and to Kinkozan studio, the largest producer of Satsuma-style products during the Meiji and Taisho period. The Kinkozan studio ceased to exist after the death of the last Kinkozan in 1927, so at the end of Taisho period. Although also in the 1930s and later, Satsuma pottery was made, this period is, with some exceptions, less interesting for collectors. This website therefore also focuses on Satsuma pottery from the Meij and Taishoperiode, which coincides with the history of the Kinkozan studio.

Kyoto-Satsuma ware and Kinkozan

Kyoto had a long tradition in pottery, dating back from the early 1600’s. These kilns were built along the eastern mountains of Kyoto at Awataguchi, Kiyomizu and Otowa, which became the centers of Kyoto ware. Most of the kilns were located in Awata, where according to documents from that time, the fire in the kilns were burning day and night, trying to meet the enormous demand for Satsuma ware. Kyoto was one of the most successful and largest producers of Satsuma-like ware in a style that became known as Kyo-Satsuma. Kyo-Satsuma received high reputation from abroad after the World Expo in Paris because it was attractive, colorful and appealing to western taste

The painting technique used in Kyoto’s Satsuma-style ware was developed by Kinkōzan Sōbei lV (1824–1884), the sixth generation of a family of Kyoto Awataguchi potters with the name Koboyashi.

Note that that Kinkōzan Sōbei lV (1824–1884), was the sixth generation of a family of Kyoto Awataguchi potters with the name Koboyashi / studioname Kagiya (see: Japanese Biographical Index, B. Wispelwey, Muchen 2004 ). In the 18th century the third Koboyashi was granted by the Shogun to bear the name Kinkozan. So the line of potters with the name Kobyashi starts two generations before the Kinkozan name was granted to this family. That makes that Kinkozan IV erroniously also is known as Kinkozan VI, and his son, the last Kinkozan as Kinkozan VII)-Kinkozan Sobei IV was appointed as the official potter for the Tokugawa shogunate and his kiln flourished in those years. But as a result of the Meiji restoration, he lost important clients such as the shogun, daimyo and other nobles who lost their former position or moved to the new capital Edo. To find new customers, he established trade relationships with foreign exporters who lived in Kobe and invested in refining the painting method for pottery and decoration, which ultimately resulted in "Kyo-Satsuma" ware, characterized by delicate, sometimes breathtaking detailed brushwork in multicolored glazes and gold on a crackled ivory white earthenware body.

Reticulated vase by Kinkozan

After the death of Kinkozan Sobei IV, the studio was passed on to his son Kinkōzan Sōbei V (1868-1927), who further developed the Kyō Satsuma techniques and succeeded in becoming the largest producer of Satsuma ware of that time but also a producer of some of the best quality Satsuma items. But the demand for Satsumaware completely changed the way of production and the time given to artisans to realize the goods. Satsuma was produced in huge quantities and most factories of Satsuma products only served western households with cheap mass production, without any interest in quality. The latter can best be illustrated by an eyewitness report of Edward Samuel Morse, around 1880 (quoted in Japanese ceramics of the last 100 years, by Irene Stitts):

“ The entrance to the potteries was reserved and modest; and within we were greeted by the head of the family and tea and cakes were immidiately offered us. It seems that members of the family alone are engaged on this work; from the little boy or girl to the grandfather, whose feeble strength is utilized in some simple process of the work. The output is small, except in those potteries given up to making stuff for the foreign trade, known to the Japanese as Yokohama muke; that is for export, a contemptuous expression. In many cases outsiders are employed; boys often ten years old splashing on the decoration of flowers and butterflies, and the like; motives derived from their mythology, but in sickening profusion, so contrary to the exquisite reserve of the Japanese in the decoration of objects for their own use. Previous to the demands of the foreigner the members of the immediate family were leisurely engaged in producing pottery reserved in formand decoration. Now the whole compound is given over to feverish activity of work, with every Tom, Dick and Harry and their children slapping it out by the gross. An order is given by the agent for a hundred thousand cups and saucers. “Put in all the red and green you can” is the order as told me by the agent, and the haste and roughness of the work confirms the Japanese that they are dealing with people whose taste are barbaric.”

The situation described by Morse applied to many of the potteries and studios that produced Satsumaware in later Meiji times, and the inferior results can be seen every day at sites such as ebay, at flea markets and garage sales. It is clearly not the type of Satsuma pottery, which is interesting for a collector. But Satsuma objects can be found in a wide range of quality, from the worst to the highest level, depending on the intentions of the manufacturer and the skills of the artisans involved. Although Satsuma remained a popular export product, the fascination and admiration of serious collectors for Satsumaware declined rapidly, a natural reaction after the overkill of Japan-related products in the years of Japonism. At the 1893 Colombian exhibition inChigago, the criticisms of Satsumaware were negative due to the lack of artistic development since the exhibitions in previous years. Kinkozan Sobei V, who succeeded the factory after his father's death in 1884, was shocked by the negative critics, but also impressed by the new techniques and stylish innovations on Western ceramics. He decided to invest in research and experiments, hired Western scientists to set up new techniques and experiments with materials and employed some of the best artists for new designs and decorations, influenced by the Art Nouveau and later Art Deco movement. He experimented with monochromes and other new types of decoration on both porcelain and eathenware, and tried out all possible styles, from large palacevases suitable for the old Victorian houses, to miniature items, real gems of only 6 cm high. Some of his best objects were made in the late Meiji and Taisho period.

Taizan Yohei XII pair of vases with decor of flowers, foliage and butterflies on a graded blue to green ground.

There were more artists like Kinkozan who did not fully sacrifice their quality standards to meet the huge demand for Satsumaware. Taizan Yohei, Kinkozan, Chin Jukan, Seikozan, Yabu Meizan, Ryozan end Miyagawa Kozan produced real masterpieces during the Meiji period and later. But in addition to these most famous artists, there were many other artists who produced Satsuma goods at a consistently good quality level: Hattori, Hododa, Meigyokuzan, Sozan, Kaizan, Genzan, Fuzan, and many others were able to produce the highest quality, although not every object can meet this qualification. Just like Kinkozan, they had to produce lower quality Satsuma items in order to survive in a shrinking market. A very high quality object can sometimes take months to realize, and for most of the kilns, studio’s or factories this was no longer a realistic option in a market that was subject to the changing taste of customers and strong competition from hundreds of smaller and larger factories and studios. The Kinkozan studio ceased to exist after the death of Kinkozan V in 1927.

During the Taisho period there was a further decline in the demand for Satsuma pottery.There is of course no clear separation between the Meiji and the Taisho period, such terms are only intended to give an indication of the differences that can be observed over time. And it must be said that a great deal of beautiful work still was made in the Taisho period. The Kinkozanstudio closed in 1932 (after the death of Kinkozan VII in 1927, at the end of the Taisho period), Yabu Meizan worked until his death in 1934, and also after the death of the famous Chin Jukan XII in 1906 and Ito Tozan in 1920 excellent work was made by their descendants.

Kinkozan vases in Art Deco style from the Taisho period

Due to the outbreak of the First World War, exports to Europe and the United States stagnated, and although the following years were characterized by high economic activity in the United States, where there was of unbridled economic growth, this did not lead to more interest in high-quality Satsuma ware. The rich westerners who could afford these pieces and for whom it was intended had lost their interest in Japan, and more and more the emphasis was shifting to the production of cheap, quickly fabricated products of inferior quality. In the 1930s, after the Stock Market Crash of 1929, that only became worse.

In the 1920s and early 1930s, economic setbacks led Japan to fall under the increasing influence of ultra-nationalist, expansionist military leaders. This led to the invasion of Manchuria (1931) and a second Sino-Japanese War (1937), the prelude to the second world war. After the war, there was only increased production for the benefit of the many American soldiers who were stationed there and wanted to take home a souvenir. Although Japanese ceramics in general may be called innovative after the second world war under the influence of the Sodeisha movement, this does not apply to Satsuma pottery.

With the exception of only a few potteries, nowadays lead bij the descendants of Chin Jukan or Tozan the production of serious Satsuma work focused on quality and artistry only recently has started again. So high-level Satsuma work is still being made, but mostly on a very small scale by masters as Tamie Ono (b.1955), who produce traditional Kyo-Satsuma ware of the highest quality as well as miniatures painted on porcelain, which she called Hana Satsuma (gorgeous Satsuma). In her work she combines new designs and ideas with the traditional technique of Kyoto Satsuma. (See also: modern Satsuma masters) However, for the average western collector of Satsuma pottery, the Meiji and Taisho period remains the most important era's.

A Hana Satsuma cup by contemporary master Tamie Ono

To conclude this short history: Remember that most of the kind of Satsuma pottery that we admire and collect today was explicitly intended for export to Europe and the United States, and it is precisely here in the West that Satsuma pottery from the Meiji and Taisho period is abundantly present. That makes collecting possible, it's just here! The most important question is therefore not where Satsuma pottery can be found, but how to distinguish between good and bad quality. And it is very satisfying to find a little gem among that large amount of mediocre or even inferior products.

This site does not provide the full history of Satsuma pottery. The historical background and development of Satsuma ware can be found on the internet or in books. For those who are interested, click on the Good books and useful websites page.

For a more detailed description of Japanese ceramics in general, please click here: https://www.gendai-tojiki.com/a-brief-history-of-japanese-ceramics

Reactie plaatsen

Reacties